-

Stéréotype du noir dans la littérature antillaise Guadeloupe-Martinique, thèse pour le doctorat de 3ème cycle

Stéréotype du noir dans la littérature antillaise Guadeloupe-Martinique, thèse pour le doctorat de 3ème cycle

-

Les Pharisiens, tapuscrit du roman

Les Pharisiens, tapuscrit du roman Les Pharisiens est un court roman écrit par Maryse Condé en 1962, alors qu’elle n’a que 25 ans, vient d’arriver en Guinée avec ses enfants et s’apprête à passer une partie de sa vie en Afrique. La future écrivaine ne l’ayant pas jugé assez bon pour être publié, ce premier texte est resté inédit et inconnu du grand public comme des chercheurs pendant plus de 50 ans.

L’intrigue se déroule en Guadeloupe, dans les années 50 ou 60. Elle entremêle les destins de trois familles issues de milieux sociaux très différents. Le lecteur y découvre une société guadeloupéenne clivée entre discrimination par la couleur et discrimination par l’argent et fossilisée dans le jeu des apparences sociales.

Le tapuscrit dactylographié, dont les toutes dernières pages sont manquantes, est corrigé de la main de Maryse Condé elle-même après discussions en Guinée et au Ghana avec Françoise Didon, une amie guadeloupéenne.

-

Appendice

Appendice

-

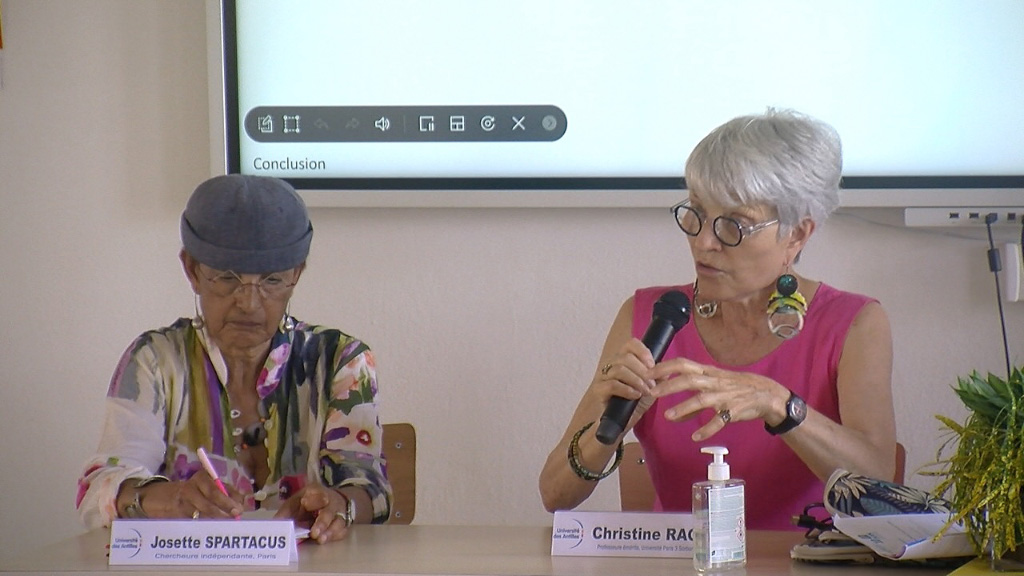

Synthèse et conclusion du colloque

Synthèse et conclusion du colloque

-

Le Black Arts Movement et la L.A. Rebellion à Los Angeles : africanité et mémoire de l'esclavage comme enjeux de l'esthétique visuelle afroaméricaine

Le Black Arts Movement et la L.A. Rebellion à Los Angeles : africanité et mémoire de l'esclavage comme enjeux de l'esthétique visuelle afroaméricaine

-

Décoloniser les mémoires de l'esclavage à l'école : la réhabilitation des figures esclavisé.es

Décoloniser les mémoires de l'esclavage à l'école : la réhabilitation des figures esclavisé.es

-

Discussion

Discussion

-

Contextualiser les mémoires de l'esclavage : transmissions transgénérationnelles dans Homegoing de Yaa Gyasi

Contextualiser les mémoires de l'esclavage : transmissions transgénérationnelles dans Homegoing de Yaa Gyasi

-

Mémoire de chair et mémoire de papier : vivre et raconter l'Histoire dans Biblique des derniers gestes de Patrick Chamoiseau

Mémoire de chair et mémoire de papier : vivre et raconter l'Histoire dans Biblique des derniers gestes de Patrick Chamoiseau

-

« Any niggerwoman can become a Black woman in secret » : mémoires et représentations des modes de résistance féminine sous l'esclavage dans les œuvres de Marlon James et de Michelle Cliff

« Any niggerwoman can become a Black woman in secret » : mémoires et représentations des modes de résistance féminine sous l'esclavage dans les œuvres de Marlon James et de Michelle Cliff

-

Discussion

Discussion

-

Archives littéraires de l'asservissement / Mémoires et syndrome de stress post-traumatique du Monde / Trans-lations / Trans-relations

Archives littéraires de l'asservissement / Mémoires et syndrome de stress post-traumatique du Monde / Trans-lations / Trans-relations

-

La traduction participe-t-elle au « devoir / droit de mémoire » ?

La traduction participe-t-elle au « devoir / droit de mémoire » ?

-

Discussion

Discussion

-

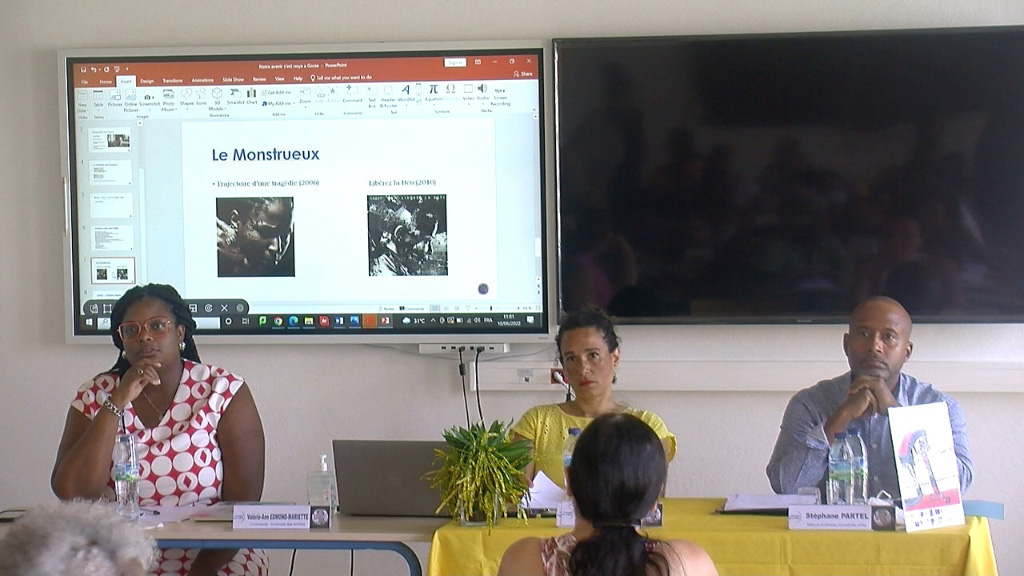

« Notre avenir s'est noyé à Gorée » : le rap français entre résistance et mémoire

« Notre avenir s'est noyé à Gorée » : le rap français entre résistance et mémoire

-

Les chansons de Gérard La Viny ou l'existence d'une mémoire de l'esclavage doudouiste ?

Les chansons de Gérard La Viny ou l'existence d'une mémoire de l'esclavage doudouiste ?

-

Discussion

Discussion

-

Monuments de l'histoire de la Confédération aux Etats-Unis et mémoire de l'esclavage

Monuments de l'histoire de la Confédération aux Etats-Unis et mémoire de l'esclavage

-

Archéologie d'une politique mémorielle : Aimé Césaire à Fort-de-France

Archéologie d'une politique mémorielle : Aimé Césaire à Fort-de-France

-

Décoloniser les mémoires de l'esclavage à La Nouvelle-Orléans : anatomie d'un palimpseste à visée radicale

Décoloniser les mémoires de l'esclavage à La Nouvelle-Orléans : anatomie d'un palimpseste à visée radicale

-

The Underground Railroad (Barry Jenkins, 2021) : décoloniser le passé de l'esclavage par la sérialité

The Underground Railroad (Barry Jenkins, 2021) : décoloniser le passé de l'esclavage par la sérialité

-

The Language of Memory in Wilson Harris' Fiction

The Language of Memory in Wilson Harris' Fiction

-

The New Conversation On Race in America in Show me a Hero (David Simon, 2015) and The Goord Fight (Robert et Michelle King, 2017)

The New Conversation On Race in America in Show me a Hero (David Simon, 2015) and The Goord Fight (Robert et Michelle King, 2017)

-

Discussion

Discussion

-

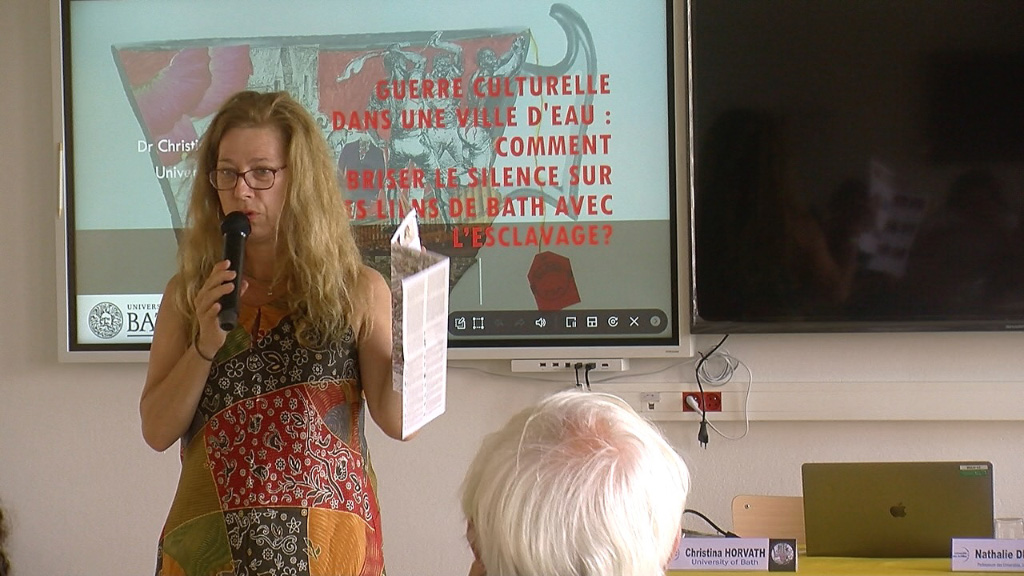

Guerre culturelle dans une ville d'eau : comment briser le silence tenace sur le passé esclavagiste de Bath ?

Guerre culturelle dans une ville d'eau : comment briser le silence tenace sur le passé esclavagiste de Bath ?

-

Commemoration of Enslavement and Histories of Dehumanisation from a Dutch and Social Art Pratice Perspective

Commemoration of Enslavement and Histories of Dehumanisation from a Dutch and Social Art Pratice Perspective

-

Discussion

Discussion

-

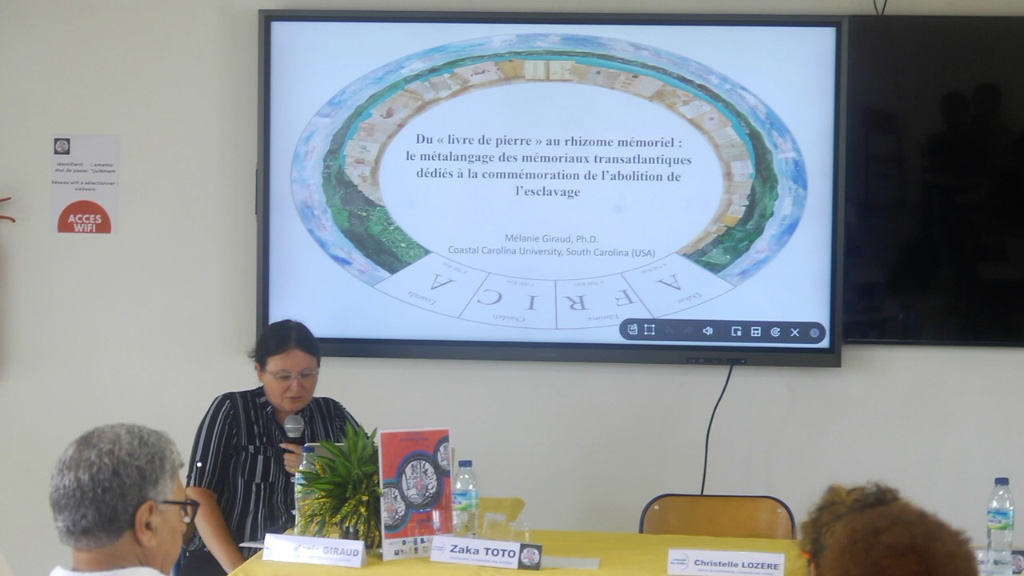

Du « livre de pierre » au rhizome mémoriel : le métalangage des mémoriaux transatlantiques dédiés à la commémoration de l'abolition de l'esclavage

Du « livre de pierre » au rhizome mémoriel : le métalangage des mémoriaux transatlantiques dédiés à la commémoration de l'abolition de l'esclavage

-

Statuaire, mémoire et turfu

Statuaire, mémoire et turfu

-

Discussion

Discussion

-

De la Traite à la Relation. Espaces mémoriels et traumas historiques dans West Indies (Med Hondo) et Révolution Zendj (Tariq Teguia)

De la Traite à la Relation. Espaces mémoriels et traumas historiques dans West Indies (Med Hondo) et Révolution Zendj (Tariq Teguia)

-

Cinéma antillais et Tropiques amers : deux volets de la mise en scène des mémoires de l'esclavage

Cinéma antillais et Tropiques amers : deux volets de la mise en scène des mémoires de l'esclavage

-

Lovecraft Country et la réappropriation de la culture pop blanche : hybridité générique et discours politique

Lovecraft Country et la réappropriation de la culture pop blanche : hybridité générique et discours politique

-

Discussion

Discussion

-

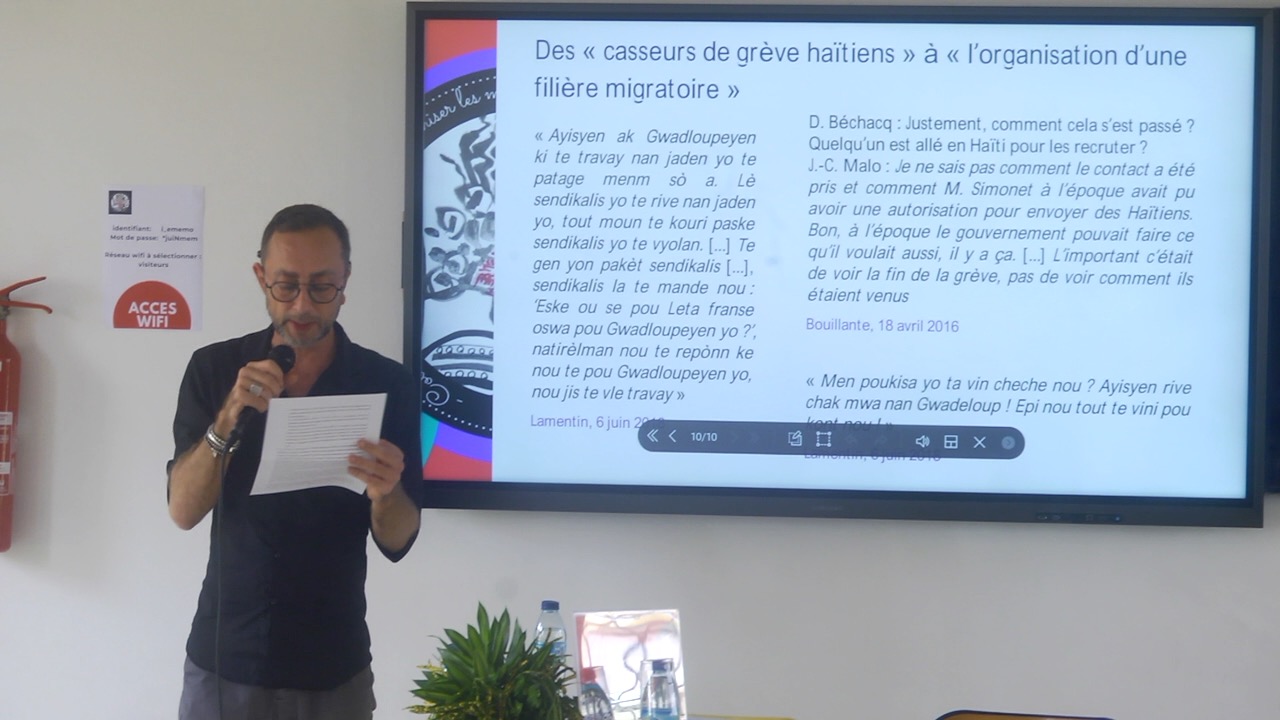

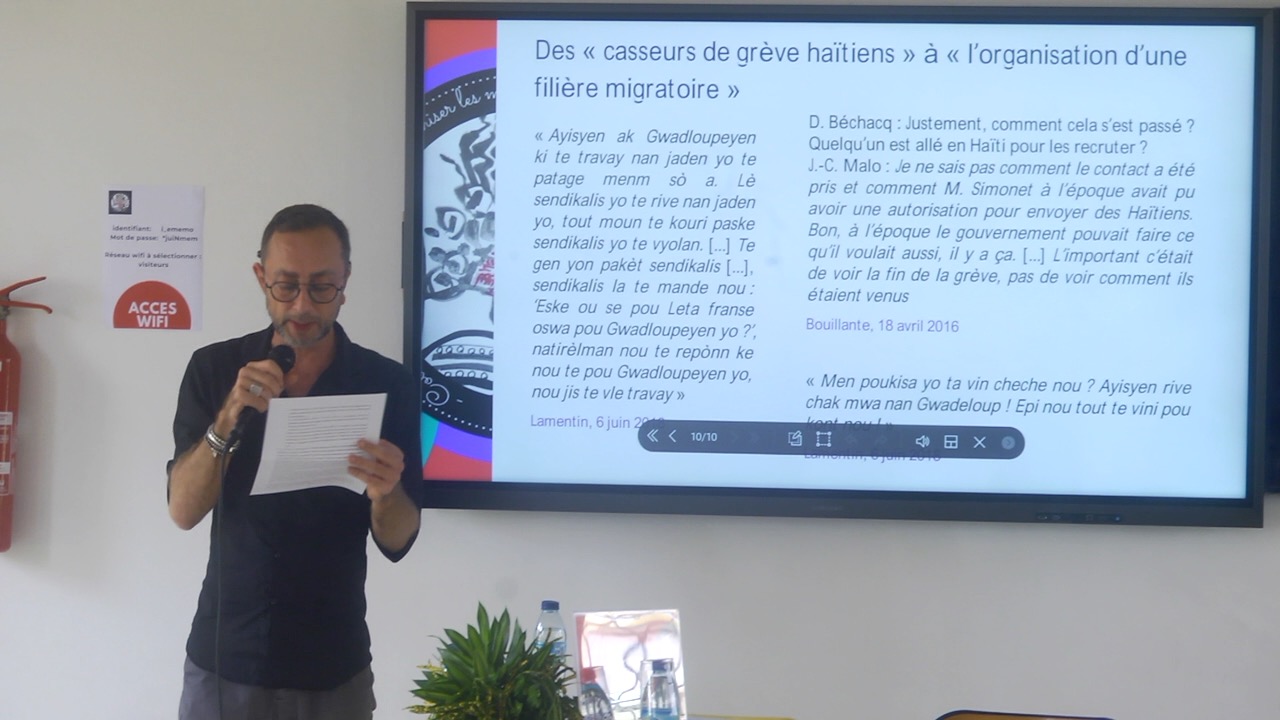

Ressusciter la figure de l'esclave dans les luttes syndicales et indépendantistes. Aux origines supposées de la migration haïtienne en Guadeloupe (années 1970)

Ressusciter la figure de l'esclave dans les luttes syndicales et indépendantistes. Aux origines supposées de la migration haïtienne en Guadeloupe (années 1970)

-

Mémoire coloniale et/ou mémoire de la résistance à l'ordre colonial dans l'espace public (Antilles, Guyane, Surinam): les limites de la pensée décoloniale

Mémoire coloniale et/ou mémoire de la résistance à l'ordre colonial dans l'espace public (Antilles, Guyane, Surinam): les limites de la pensée décoloniale

-

Discussion

Discussion

-

Corps sans sépultures : entre-deux mémoriel et réinscription dans Kindred et Prison d'ébène

Corps sans sépultures : entre-deux mémoriel et réinscription dans Kindred et Prison d'ébène

-

La malemort mémorante de René Beauregard (1975-1982)

La malemort mémorante de René Beauregard (1975-1982)

-

Déplacements, transfigurations: de quelques réécritures fictionnelles et artistiques comme métabolisations émancipatrices des mémoires de l'esclavage transatlantique

Déplacements, transfigurations: de quelques réécritures fictionnelles et artistiques comme métabolisations émancipatrices des mémoires de l'esclavage transatlantique

-

Lieux de mémoire et esthétique du trauma

Lieux de mémoire et esthétique du trauma

-

De Ouidah à Minneapolis: la mémoire décolonisée de l'Africain-Américain Colson Whitehead

De Ouidah à Minneapolis: la mémoire décolonisée de l'Africain-Américain Colson Whitehead

-

"La peau d'un Blanc pour parchemin, son crâne pour écritoire": revendiquer la tradition radicale noire.

"La peau d'un Blanc pour parchemin, son crâne pour écritoire": revendiquer la tradition radicale noire.

-

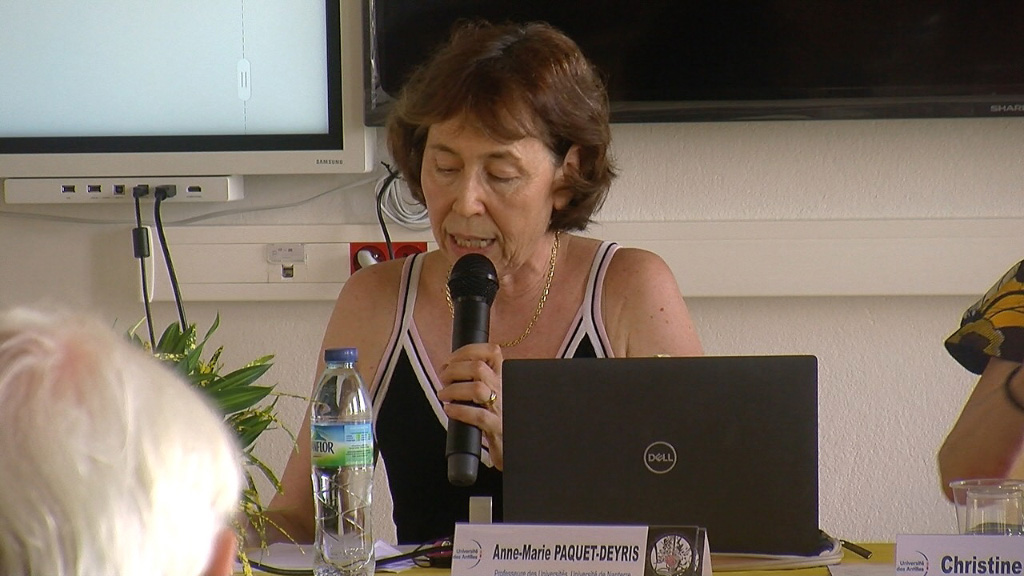

Ouverture officielle du colloque

Ouverture officielle du colloque

-

Structure pitt Saint-Pierre, 2010. [04]

Structure pitt Saint-Pierre, 2010. [04]

-

Structure pitt Saint-Pierre, 2010. [03]

Structure pitt Saint-Pierre, 2010. [03]

-

Structure pitt Saint-Pierre, 2010. [02]

Structure pitt Saint-Pierre, 2010. [02]

-

Structure pitt Saint-Pierre, 2010. [01]

Structure pitt Saint-Pierre, 2010. [01]

-

Structure baie des mulets, 2010. [02]

Structure baie des mulets, 2010. [02]

-

Structure baie des mulets, 2010. [01]

Structure baie des mulets, 2010. [01]

-

Pitt Colonette caloges Ducos, 2010. [02]

Pitt Colonette caloges Ducos, 2010. [02]

-

Pitt Colonette structure Ducos, 2010. [01]

Pitt Colonette structure Ducos, 2010. [01]

-

Pitt Casérus structure Sainte-Marie, 2010. [02]

Pitt Casérus structure Sainte-Marie, 2010. [02]

-

Pitt Casérus structure Sainte-Marie, 2010. [01]

Pitt Casérus structure Sainte-Marie, 2010. [01]

-

Nicole Jean-Baptiste, propriétaire du pitt Malgré-Tout, Saint-Pierre, 2010.

Nicole Jean-Baptiste, propriétaire du pitt Malgré-Tout, Saint-Pierre, 2010.

-

Maurice Delivry dit Gros-Maurice, ancien propriétaire de pitt, meneur de séance, Le Lamentin, 2010

Maurice Delivry dit Gros-Maurice, ancien propriétaire de pitt, meneur de séance, Le Lamentin, 2010

-

Christelle Crusol & Francky Quatrevent, éleveurs, Le Vauclin, 2010

Christelle Crusol & Francky Quatrevent, éleveurs, Le Vauclin, 2010

-

Nicole Souffran, éleveur et meneur de séance, pitt Pont-Vert, Morne Gommier, Le Marin, 2010.

Nicole Souffran, éleveur et meneur de séance, pitt Pont-Vert, Morne Gommier, Le Marin, 2010.

-

Frantz & Wenceslas Viersac, éleveurs, Choco, Saint-Joseph, 2010.

Frantz & Wenceslas Viersac, éleveurs, Choco, Saint-Joseph, 2010.

-

Lucien Saxemard, petit éleveur, Fort-de-France, 2010.

Lucien Saxemard, petit éleveur, Fort-de-France, 2010.

-

Éric Rosemain, éleveur et propriétaire du pitt Thomassin, Barrière-la-croix, Sainte-Anne, 2011.

Éric Rosemain, éleveur et propriétaire du pitt Thomassin, Barrière-la-croix, Sainte-Anne, 2011.

-

Fernand Rinto, propriétaire du pitt Pont-Vert, Le Lamentin, 2010.

Fernand Rinto, propriétaire du pitt Pont-Vert, Le Lamentin, 2010.

-

M. Pinel, éleveur et meneur de séances au pitt Flamboyant, Baie des Mulets, Le Vauclin, 2010.

M. Pinel, éleveur et meneur de séances au pitt Flamboyant, Baie des Mulets, Le Vauclin, 2010.

-

Félix Casérus, propriétaire du pitt Central Libre, Sainte-Marie, 2010.

Félix Casérus, propriétaire du pitt Central Libre, Sainte-Marie, 2010.

-

Baby Coco, éleveur et soigneur, Le Robert, 2010.

Baby Coco, éleveur et soigneur, Le Robert, 2010.

-

Lise-Anne Voltine & ses filles (Magalie, Rose-Hélène, Léandre), propriétaire du pitt Flamboyant, Baie des Mulets, Le Vauclin, 2010.

Lise-Anne Voltine & ses filles (Magalie, Rose-Hélène, Léandre), propriétaire du pitt Flamboyant, Baie des Mulets, Le Vauclin, 2010.

-

Didière & Eddy Hardy-Dessources, éleveurs et anciens propriétaires de pitt, Ajoupa-Bouillon, 2010.

Didière & Eddy Hardy-Dessources, éleveurs et anciens propriétaires de pitt, Ajoupa-Bouillon, 2010.

-

Mesmin Moderne dit Minmin, éleveur et meneur de séance, & Pierre Moncoq, soigneur, Saint-Pierre, 2010.

Mesmin Moderne dit Minmin, éleveur et meneur de séance, & Pierre Moncoq, soigneur, Saint-Pierre, 2010.

-

Objets pitt - soins, 2011.

Objets pitt - soins, 2011.

-

Objet pitt - épron synthétique, 2011.

Objet pitt - épron synthétique, 2011.

-

Objet pitt - épron, 2011. [02]

Objet pitt - épron, 2011. [02]

-

Objet pitt - bague, 2011.

Objet pitt - bague, 2011.

-

Objet pitt - soins, 2011. [02]

Objet pitt - soins, 2011. [02]

-

Objets pitt - soins alimentation, 2011.

Objets pitt - soins alimentation, 2011.

-

Objet pitt - protection d'entrainement, 2011.

Objet pitt - protection d'entrainement, 2011.

-

Objet pitt - soins, 2011. [01]

Objet pitt - soins, 2011. [01]

-

Objet pitt - épron et support, 2011.

Objet pitt - épron et support, 2011.

-

Objet pitt - éperon, 2011. [01]

Objet pitt - éperon, 2011. [01]

-

Pitt preparation coq, 2010.

Pitt preparation coq, 2010.

-

Eleveur - Mr Saxemard, 2010.

Eleveur - Mr Saxemard, 2010.

-

Soins des blessures d'un coq, 2010.

Soins des blessures d'un coq, 2010.

-

Serie pitt - Mme Agot eleveur, 2010.

Serie pitt - Mme Agot eleveur, 2010.

-

Combat coq, 2010.

Combat coq, 2010.

-

Pitt - les paris, 2010. [03]

Pitt - les paris, 2010. [03]

-

Pitt - les paris, 2010. [02]

Pitt - les paris, 2010. [02]

-

Pitt - les paris, 2010. [01]

Pitt - les paris, 2010. [01]

-

Pitt - ambiance la pesées, 2010.

Pitt - ambiance la pesées, 2010.

-

Pitt - combat, 2010.

Pitt - combat, 2010.

-

Pitt - ambiance, 2010.

Pitt - ambiance, 2010.

-

Femme au pitt, 2010. [02]

Femme au pitt, 2010. [02]

-

Femme au pitt, 2010. [01]

Femme au pitt, 2010. [01]

-

Combat de coq, 2010.

Combat de coq, 2010.

-

HOINDEH family on the beach in Hewé, during a private ceremony of the MAMI TCHAMBA cult, the only Voodoo cult to question the memory of African slaves.

HOINDEH family on the beach in Hewé, during a private ceremony of the MAMI TCHAMBA cult, the only Voodoo cult to question the memory of African slaves. The history of the Atlantic slave trade is not very active in Africa in a narrative form but it has found other forms of expression. Historical narrative and memory of the past are a part of the ritual space: the body is “owned” in the dance and music, in the incantations, in the process of divination and magic items. The Tchamba cult is one of the most significant expressions of this ritual heritage. It is represented among the populations of Ewe and Mina dialects in the coastal areas of Ghana, Togo and Benin. It is a voodoo cult dedicated to slaves, where the spirits of those who died in captivity and far from their motherland are worshiped. Ironically, those spirits have chosen their former masters’ descendants to take care of the Tchamba altar as well as their bodies, which they possess during ceremonies.

-

GRAFFITI in Da Silva Museum of Arts and culture, Porto Novo, Benin.

GRAFFITI in Da Silva Museum of Arts and culture, Porto Novo, Benin. Although, according to Urban-Karim-Elisio da Silva’s story, he was a descendant of a slave trader, on his father’s side, he rather identifies himself as a descendant of a slave, through his mother’s family, Paraiso. In his case, being the descendant of a slave becomes a source of pride and generates a political capital, in order to increase the legitimacy of his museum. Porto Novo, Benin

-

CLEMENT OLIVIER DE MONTAGUERE, descendant of Olivier de Montaguere in the family cemetery, Ouidah.

CLEMENT OLIVIER DE MONTAGUERE, descendant of Olivier de Montaguere in the family cemetery, Ouidah. Clement is a member of this family originally from Marseille, France. His ancestor, Olivier de Montaguere, was the nineteenth steward of the French Fort for Louis XVI. He arrived in Ouidah in 1776. He brought with him his wife and their three children, Joseph, Nicolas and Jean Baptiste and organized the slave trade with the French West Indies, «He disappeared during one of his trips to the Caribbean and he is never returned to Ouidah» said Clement Olivier of Montaguere. Their descendents still live today in the old compound of their ancestor. Unlike many other local families, they have no voodoo altars in their homes, and while claiming their European origins, they strictly observe the catholic religion. Today, in the family cemetery (where I got the pictures), the oldest tomb is to Nicolas Olivier de Montaguere’s. According to the tradition, Nicolas grew up with the king of Dahomey Agonglo (1789-1797). After his adolescence spent in Abomey with the king, he returned to Ouidah in his father’s family home when he continued to deal palm oil . Nicolas and Joseph’s descendants still live in the old compound of their ancestors. They have maintained a position of prestige in the society, and historically occupy important positions in the public administration. Ouidah, Benin.

-

Honorè Feliciano DE SOUZA, CHACHA VIII in the memorial of Chacha I, Ouidah.

Honorè Feliciano DE SOUZA, CHACHA VIII in the memorial of Chacha I, Ouidah. Honore Feliciano de Souza is the current head of the Aguda community and the direct heir of Don Francisco Felix de Souza, Chacha I (1754-1848), the foremost middle-men in the slave trade between the Kingdom of Dahomey and the Europeans, early XIXth century. To honor their ancestor, the family has a memorial in Singbomey, with the tomb of Chacha I. This memorial existed for many years, but became accessible to the public only in the 1990s. Paradoxically, slavery heritage official projects also helped to promote the memory of the slave merchant Francisco Felix de Souza. According to Honore Feliciano‘s unlikely opinion, “the Chacha was not involved in such a slave trade as this. At the time when the Kingdom of Dahomey was killing people, he preferred to take them to Brazil to make them work. He was in fact saving people and that is the reason why today there is some admiration for him,” he says. “Nowadays, no one would want to be a Chacha. Being Chacha is facing many hardships. I haven’t chosen to be one. On October 1995, everyone gathered here and I was appointed Chacha VIII, I cried that day. It’s a life-long mandate.” Ouidah, Benin.

-

His majesty MITO DAHO KPASSÈNON, king of Ouidah and supreme head of the voodoo cult, sitting in the Audience hall, Royal Palace.

His majesty MITO DAHO KPASSÈNON, king of Ouidah and supreme head of the voodoo cult, sitting in the Audience hall, Royal Palace. Mito Daho Kpassenon is a member of one of the oldest families of Benin, heir and descendant of King Kpassé, the first one to make business with the Europeans, particularly through the slave trade, when the Portuguese arrived in the Benin Bay around 1580. “According to the oral tradition, KPaté, one of the king’s servants, was fishing crabs on the shore when he saw white people on the beach. He took them to King KPASSE, and from that day they started trading,” tells King Kpassenon. In the early 1990s, relying on the cultural and religious exchanges established during the period of the Atlantic slave trade, and in parallel with the debates aimed at developing the Slave Route Project, he joined the project “Ouidah 92”, the world festival of voodoo culture. Like the president Songlo, by promoting the Vodun religion and the exchanges between Africa and the Americas, he presented slavery and the Atlantic slave trade not as a rupture between generations, families, and traditions but as events that produced continuity across the Atlantic. Ouidah, Benin.

-

The apex of the Slaves’ Route is the «GATE OF NO RETURN», the only monument in Ouidah sponsored by the Slave Route Project. Situated at the end of the road, on the beach, the imposing gate was unveiled in November 1995, and still attracts numerous tourists and leading foreign visitors, such as the Brazilian President, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva who visited the monument during his travel to the country in 2006.

The apex of the Slaves’ Route is the «GATE OF NO RETURN», the only monument in Ouidah sponsored by the Slave Route Project. Situated at the end of the road, on the beach, the imposing gate was unveiled in November 1995, and still attracts numerous tourists and leading foreign visitors, such as the Brazilian President, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva who visited the monument during his travel to the country in 2006. The monument, designed and ornamented by Beninese artist Fortune Bandeira, evokes the monumental Soviet aesthetics that dominated the country’s public monuments until the beginning of the 1990s. Placed on a large cement platform, higher than the level of the ground, the Gate’s arcade marks the transition between the beach and the Atlantic Ocean, which is visible through it. On each side of the gate, giant copper sculptures created by Gnonnou Dominique Kouass, represent a group of captives breaking their chains. Close to the monument, tourists can stop at a kiosk to buy “African” sculptures, wooden masks, jewellery, and calabashes. In addition to these “authentic” objects, the visitors can also buy actual Vodun fetishes, taken from neighbouring temples. Ouidah, Benin.

-

Ahi, doing some repairs on the “Slaves’ Route”.

Ahi, doing some repairs on the “Slaves’ Route”. The Slaves’ Route is a two-miles road starting in downtown Ouidah, close to a former slave market, and ending at the beach, where the captives were allegedly put on pirogues that brought them to the slave ships. In fact, because the coastal lagoon separated the town from the shore, it is more likely that the captives covered part of the way to the outer shore by canoe. Despite the relative success of the Slaves’ Route, only the local population living in the neighbourhoods is sufficiently audacious to walk along the road. The two-miles road is long and because the traffic is intense and there is no allotted space for pedestrians, it is rather difficult to safely observe the monuments. Indeed, individual tourists experience the Slaves’ Route by zemidjan (local motorcycle taxis). If with groups, they see the route by car or bus, and stop only at the end of the road, at the beach. Ouidah, Benin

-

A detention cell for reluctant slaves, according to Philip Atta-Tawson’s story, Fort William, Anomabu.

A detention cell for reluctant slaves, according to Philip Atta-Tawson’s story, Fort William, Anomabu. Philip Atta-Tawson is today the keeper of the place where he lives with his family. In most castles of Ghana, there is a family living and working as a custodian on behalf of the government. An estimated half million of captives were sent from Anomabu to the Americas, among which 30 000 to the French West Indies. In the past, the fort was then used as a jail, then a post office, until it became a national registered site. Anomabu, Ghana

Stéréotype du noir dans la littérature antillaise Guadeloupe-Martinique, thèse pour le doctorat de 3ème cycle

Stéréotype du noir dans la littérature antillaise Guadeloupe-Martinique, thèse pour le doctorat de 3ème cycle  Les Pharisiens, tapuscrit du roman Les Pharisiens est un court roman écrit par Maryse Condé en 1962, alors qu’elle n’a que 25 ans, vient d’arriver en Guinée avec ses enfants et s’apprête à passer une partie de sa vie en Afrique. La future écrivaine ne l’ayant pas jugé assez bon pour être publié, ce premier texte est resté inédit et inconnu du grand public comme des chercheurs pendant plus de 50 ans. L’intrigue se déroule en Guadeloupe, dans les années 50 ou 60. Elle entremêle les destins de trois familles issues de milieux sociaux très différents. Le lecteur y découvre une société guadeloupéenne clivée entre discrimination par la couleur et discrimination par l’argent et fossilisée dans le jeu des apparences sociales. Le tapuscrit dactylographié, dont les toutes dernières pages sont manquantes, est corrigé de la main de Maryse Condé elle-même après discussions en Guinée et au Ghana avec Françoise Didon, une amie guadeloupéenne.

Les Pharisiens, tapuscrit du roman Les Pharisiens est un court roman écrit par Maryse Condé en 1962, alors qu’elle n’a que 25 ans, vient d’arriver en Guinée avec ses enfants et s’apprête à passer une partie de sa vie en Afrique. La future écrivaine ne l’ayant pas jugé assez bon pour être publié, ce premier texte est resté inédit et inconnu du grand public comme des chercheurs pendant plus de 50 ans. L’intrigue se déroule en Guadeloupe, dans les années 50 ou 60. Elle entremêle les destins de trois familles issues de milieux sociaux très différents. Le lecteur y découvre une société guadeloupéenne clivée entre discrimination par la couleur et discrimination par l’argent et fossilisée dans le jeu des apparences sociales. Le tapuscrit dactylographié, dont les toutes dernières pages sont manquantes, est corrigé de la main de Maryse Condé elle-même après discussions en Guinée et au Ghana avec Françoise Didon, une amie guadeloupéenne. Appendice

Appendice  Synthèse et conclusion du colloque

Synthèse et conclusion du colloque  Le Black Arts Movement et la L.A. Rebellion à Los Angeles : africanité et mémoire de l'esclavage comme enjeux de l'esthétique visuelle afroaméricaine

Le Black Arts Movement et la L.A. Rebellion à Los Angeles : africanité et mémoire de l'esclavage comme enjeux de l'esthétique visuelle afroaméricaine  Décoloniser les mémoires de l'esclavage à l'école : la réhabilitation des figures esclavisé.es

Décoloniser les mémoires de l'esclavage à l'école : la réhabilitation des figures esclavisé.es  Discussion

Discussion  Contextualiser les mémoires de l'esclavage : transmissions transgénérationnelles dans Homegoing de Yaa Gyasi

Contextualiser les mémoires de l'esclavage : transmissions transgénérationnelles dans Homegoing de Yaa Gyasi  Mémoire de chair et mémoire de papier : vivre et raconter l'Histoire dans Biblique des derniers gestes de Patrick Chamoiseau

Mémoire de chair et mémoire de papier : vivre et raconter l'Histoire dans Biblique des derniers gestes de Patrick Chamoiseau  « Any niggerwoman can become a Black woman in secret » : mémoires et représentations des modes de résistance féminine sous l'esclavage dans les œuvres de Marlon James et de Michelle Cliff

« Any niggerwoman can become a Black woman in secret » : mémoires et représentations des modes de résistance féminine sous l'esclavage dans les œuvres de Marlon James et de Michelle Cliff  Discussion

Discussion  Archives littéraires de l'asservissement / Mémoires et syndrome de stress post-traumatique du Monde / Trans-lations / Trans-relations

Archives littéraires de l'asservissement / Mémoires et syndrome de stress post-traumatique du Monde / Trans-lations / Trans-relations  La traduction participe-t-elle au « devoir / droit de mémoire » ?

La traduction participe-t-elle au « devoir / droit de mémoire » ?  Discussion

Discussion  « Notre avenir s'est noyé à Gorée » : le rap français entre résistance et mémoire

« Notre avenir s'est noyé à Gorée » : le rap français entre résistance et mémoire  Les chansons de Gérard La Viny ou l'existence d'une mémoire de l'esclavage doudouiste ?

Les chansons de Gérard La Viny ou l'existence d'une mémoire de l'esclavage doudouiste ?  Discussion

Discussion  Monuments de l'histoire de la Confédération aux Etats-Unis et mémoire de l'esclavage

Monuments de l'histoire de la Confédération aux Etats-Unis et mémoire de l'esclavage  Archéologie d'une politique mémorielle : Aimé Césaire à Fort-de-France

Archéologie d'une politique mémorielle : Aimé Césaire à Fort-de-France  Décoloniser les mémoires de l'esclavage à La Nouvelle-Orléans : anatomie d'un palimpseste à visée radicale

Décoloniser les mémoires de l'esclavage à La Nouvelle-Orléans : anatomie d'un palimpseste à visée radicale  The Underground Railroad (Barry Jenkins, 2021) : décoloniser le passé de l'esclavage par la sérialité

The Underground Railroad (Barry Jenkins, 2021) : décoloniser le passé de l'esclavage par la sérialité  The Language of Memory in Wilson Harris' Fiction

The Language of Memory in Wilson Harris' Fiction  The New Conversation On Race in America in Show me a Hero (David Simon, 2015) and The Goord Fight (Robert et Michelle King, 2017)

The New Conversation On Race in America in Show me a Hero (David Simon, 2015) and The Goord Fight (Robert et Michelle King, 2017)  Discussion

Discussion  Guerre culturelle dans une ville d'eau : comment briser le silence tenace sur le passé esclavagiste de Bath ?

Guerre culturelle dans une ville d'eau : comment briser le silence tenace sur le passé esclavagiste de Bath ?  Commemoration of Enslavement and Histories of Dehumanisation from a Dutch and Social Art Pratice Perspective

Commemoration of Enslavement and Histories of Dehumanisation from a Dutch and Social Art Pratice Perspective  Discussion

Discussion  Du « livre de pierre » au rhizome mémoriel : le métalangage des mémoriaux transatlantiques dédiés à la commémoration de l'abolition de l'esclavage

Du « livre de pierre » au rhizome mémoriel : le métalangage des mémoriaux transatlantiques dédiés à la commémoration de l'abolition de l'esclavage  Statuaire, mémoire et turfu

Statuaire, mémoire et turfu  Discussion

Discussion  De la Traite à la Relation. Espaces mémoriels et traumas historiques dans West Indies (Med Hondo) et Révolution Zendj (Tariq Teguia)

De la Traite à la Relation. Espaces mémoriels et traumas historiques dans West Indies (Med Hondo) et Révolution Zendj (Tariq Teguia)  Cinéma antillais et Tropiques amers : deux volets de la mise en scène des mémoires de l'esclavage

Cinéma antillais et Tropiques amers : deux volets de la mise en scène des mémoires de l'esclavage  Lovecraft Country et la réappropriation de la culture pop blanche : hybridité générique et discours politique

Lovecraft Country et la réappropriation de la culture pop blanche : hybridité générique et discours politique  Discussion

Discussion  Ressusciter la figure de l'esclave dans les luttes syndicales et indépendantistes. Aux origines supposées de la migration haïtienne en Guadeloupe (années 1970)

Ressusciter la figure de l'esclave dans les luttes syndicales et indépendantistes. Aux origines supposées de la migration haïtienne en Guadeloupe (années 1970)  Mémoire coloniale et/ou mémoire de la résistance à l'ordre colonial dans l'espace public (Antilles, Guyane, Surinam): les limites de la pensée décoloniale

Mémoire coloniale et/ou mémoire de la résistance à l'ordre colonial dans l'espace public (Antilles, Guyane, Surinam): les limites de la pensée décoloniale  Discussion

Discussion  Corps sans sépultures : entre-deux mémoriel et réinscription dans Kindred et Prison d'ébène

Corps sans sépultures : entre-deux mémoriel et réinscription dans Kindred et Prison d'ébène  La malemort mémorante de René Beauregard (1975-1982)

La malemort mémorante de René Beauregard (1975-1982)  Déplacements, transfigurations: de quelques réécritures fictionnelles et artistiques comme métabolisations émancipatrices des mémoires de l'esclavage transatlantique

Déplacements, transfigurations: de quelques réécritures fictionnelles et artistiques comme métabolisations émancipatrices des mémoires de l'esclavage transatlantique  Lieux de mémoire et esthétique du trauma

Lieux de mémoire et esthétique du trauma  De Ouidah à Minneapolis: la mémoire décolonisée de l'Africain-Américain Colson Whitehead

De Ouidah à Minneapolis: la mémoire décolonisée de l'Africain-Américain Colson Whitehead  "La peau d'un Blanc pour parchemin, son crâne pour écritoire": revendiquer la tradition radicale noire.

"La peau d'un Blanc pour parchemin, son crâne pour écritoire": revendiquer la tradition radicale noire.  Ouverture officielle du colloque

Ouverture officielle du colloque  Structure pitt Saint-Pierre, 2010. [04]

Structure pitt Saint-Pierre, 2010. [04]  Structure pitt Saint-Pierre, 2010. [03]

Structure pitt Saint-Pierre, 2010. [03]  Structure pitt Saint-Pierre, 2010. [02]

Structure pitt Saint-Pierre, 2010. [02]  Structure pitt Saint-Pierre, 2010. [01]

Structure pitt Saint-Pierre, 2010. [01]  Structure baie des mulets, 2010. [02]

Structure baie des mulets, 2010. [02]  Structure baie des mulets, 2010. [01]

Structure baie des mulets, 2010. [01]  Pitt Colonette caloges Ducos, 2010. [02]

Pitt Colonette caloges Ducos, 2010. [02]  Pitt Colonette structure Ducos, 2010. [01]

Pitt Colonette structure Ducos, 2010. [01]  Pitt Casérus structure Sainte-Marie, 2010. [02]

Pitt Casérus structure Sainte-Marie, 2010. [02]  Pitt Casérus structure Sainte-Marie, 2010. [01]

Pitt Casérus structure Sainte-Marie, 2010. [01]  Nicole Jean-Baptiste, propriétaire du pitt Malgré-Tout, Saint-Pierre, 2010.

Nicole Jean-Baptiste, propriétaire du pitt Malgré-Tout, Saint-Pierre, 2010.  Maurice Delivry dit Gros-Maurice, ancien propriétaire de pitt, meneur de séance, Le Lamentin, 2010

Maurice Delivry dit Gros-Maurice, ancien propriétaire de pitt, meneur de séance, Le Lamentin, 2010  Christelle Crusol & Francky Quatrevent, éleveurs, Le Vauclin, 2010

Christelle Crusol & Francky Quatrevent, éleveurs, Le Vauclin, 2010  Nicole Souffran, éleveur et meneur de séance, pitt Pont-Vert, Morne Gommier, Le Marin, 2010.

Nicole Souffran, éleveur et meneur de séance, pitt Pont-Vert, Morne Gommier, Le Marin, 2010.  Frantz & Wenceslas Viersac, éleveurs, Choco, Saint-Joseph, 2010.

Frantz & Wenceslas Viersac, éleveurs, Choco, Saint-Joseph, 2010.  Lucien Saxemard, petit éleveur, Fort-de-France, 2010.

Lucien Saxemard, petit éleveur, Fort-de-France, 2010.  Éric Rosemain, éleveur et propriétaire du pitt Thomassin, Barrière-la-croix, Sainte-Anne, 2011.

Éric Rosemain, éleveur et propriétaire du pitt Thomassin, Barrière-la-croix, Sainte-Anne, 2011.  Fernand Rinto, propriétaire du pitt Pont-Vert, Le Lamentin, 2010.

Fernand Rinto, propriétaire du pitt Pont-Vert, Le Lamentin, 2010.  M. Pinel, éleveur et meneur de séances au pitt Flamboyant, Baie des Mulets, Le Vauclin, 2010.

M. Pinel, éleveur et meneur de séances au pitt Flamboyant, Baie des Mulets, Le Vauclin, 2010.  Félix Casérus, propriétaire du pitt Central Libre, Sainte-Marie, 2010.

Félix Casérus, propriétaire du pitt Central Libre, Sainte-Marie, 2010.  Baby Coco, éleveur et soigneur, Le Robert, 2010.

Baby Coco, éleveur et soigneur, Le Robert, 2010.  Lise-Anne Voltine & ses filles (Magalie, Rose-Hélène, Léandre), propriétaire du pitt Flamboyant, Baie des Mulets, Le Vauclin, 2010.

Lise-Anne Voltine & ses filles (Magalie, Rose-Hélène, Léandre), propriétaire du pitt Flamboyant, Baie des Mulets, Le Vauclin, 2010.  Didière & Eddy Hardy-Dessources, éleveurs et anciens propriétaires de pitt, Ajoupa-Bouillon, 2010.

Didière & Eddy Hardy-Dessources, éleveurs et anciens propriétaires de pitt, Ajoupa-Bouillon, 2010.  Mesmin Moderne dit Minmin, éleveur et meneur de séance, & Pierre Moncoq, soigneur, Saint-Pierre, 2010.

Mesmin Moderne dit Minmin, éleveur et meneur de séance, & Pierre Moncoq, soigneur, Saint-Pierre, 2010.  Objets pitt - soins, 2011.

Objets pitt - soins, 2011.  Objet pitt - épron synthétique, 2011.

Objet pitt - épron synthétique, 2011.  Objet pitt - épron, 2011. [02]

Objet pitt - épron, 2011. [02]  Objet pitt - bague, 2011.

Objet pitt - bague, 2011.  Objet pitt - soins, 2011. [02]

Objet pitt - soins, 2011. [02]  Objets pitt - soins alimentation, 2011.

Objets pitt - soins alimentation, 2011.  Objet pitt - protection d'entrainement, 2011.

Objet pitt - protection d'entrainement, 2011.  Objet pitt - soins, 2011. [01]

Objet pitt - soins, 2011. [01]  Objet pitt - épron et support, 2011.

Objet pitt - épron et support, 2011.  Objet pitt - éperon, 2011. [01]

Objet pitt - éperon, 2011. [01]  Pitt preparation coq, 2010.

Pitt preparation coq, 2010.  Eleveur - Mr Saxemard, 2010.

Eleveur - Mr Saxemard, 2010.  Soins des blessures d'un coq, 2010.

Soins des blessures d'un coq, 2010.  Serie pitt - Mme Agot eleveur, 2010.

Serie pitt - Mme Agot eleveur, 2010.  Combat coq, 2010.

Combat coq, 2010.  Pitt - les paris, 2010. [03]

Pitt - les paris, 2010. [03]  Pitt - les paris, 2010. [02]

Pitt - les paris, 2010. [02]  Pitt - les paris, 2010. [01]

Pitt - les paris, 2010. [01]  Pitt - ambiance la pesées, 2010.

Pitt - ambiance la pesées, 2010.  Pitt - combat, 2010.

Pitt - combat, 2010.  Pitt - ambiance, 2010.

Pitt - ambiance, 2010.  Femme au pitt, 2010. [02]

Femme au pitt, 2010. [02]  Femme au pitt, 2010. [01]

Femme au pitt, 2010. [01]  Combat de coq, 2010.

Combat de coq, 2010.  HOINDEH family on the beach in Hewé, during a private ceremony of the MAMI TCHAMBA cult, the only Voodoo cult to question the memory of African slaves. The history of the Atlantic slave trade is not very active in Africa in a narrative form but it has found other forms of expression. Historical narrative and memory of the past are a part of the ritual space: the body is “owned” in the dance and music, in the incantations, in the process of divination and magic items. The Tchamba cult is one of the most significant expressions of this ritual heritage. It is represented among the populations of Ewe and Mina dialects in the coastal areas of Ghana, Togo and Benin. It is a voodoo cult dedicated to slaves, where the spirits of those who died in captivity and far from their motherland are worshiped. Ironically, those spirits have chosen their former masters’ descendants to take care of the Tchamba altar as well as their bodies, which they possess during ceremonies.

HOINDEH family on the beach in Hewé, during a private ceremony of the MAMI TCHAMBA cult, the only Voodoo cult to question the memory of African slaves. The history of the Atlantic slave trade is not very active in Africa in a narrative form but it has found other forms of expression. Historical narrative and memory of the past are a part of the ritual space: the body is “owned” in the dance and music, in the incantations, in the process of divination and magic items. The Tchamba cult is one of the most significant expressions of this ritual heritage. It is represented among the populations of Ewe and Mina dialects in the coastal areas of Ghana, Togo and Benin. It is a voodoo cult dedicated to slaves, where the spirits of those who died in captivity and far from their motherland are worshiped. Ironically, those spirits have chosen their former masters’ descendants to take care of the Tchamba altar as well as their bodies, which they possess during ceremonies. GRAFFITI in Da Silva Museum of Arts and culture, Porto Novo, Benin. Although, according to Urban-Karim-Elisio da Silva’s story, he was a descendant of a slave trader, on his father’s side, he rather identifies himself as a descendant of a slave, through his mother’s family, Paraiso. In his case, being the descendant of a slave becomes a source of pride and generates a political capital, in order to increase the legitimacy of his museum. Porto Novo, Benin

GRAFFITI in Da Silva Museum of Arts and culture, Porto Novo, Benin. Although, according to Urban-Karim-Elisio da Silva’s story, he was a descendant of a slave trader, on his father’s side, he rather identifies himself as a descendant of a slave, through his mother’s family, Paraiso. In his case, being the descendant of a slave becomes a source of pride and generates a political capital, in order to increase the legitimacy of his museum. Porto Novo, Benin CLEMENT OLIVIER DE MONTAGUERE, descendant of Olivier de Montaguere in the family cemetery, Ouidah. Clement is a member of this family originally from Marseille, France. His ancestor, Olivier de Montaguere, was the nineteenth steward of the French Fort for Louis XVI. He arrived in Ouidah in 1776. He brought with him his wife and their three children, Joseph, Nicolas and Jean Baptiste and organized the slave trade with the French West Indies, «He disappeared during one of his trips to the Caribbean and he is never returned to Ouidah» said Clement Olivier of Montaguere. Their descendents still live today in the old compound of their ancestor. Unlike many other local families, they have no voodoo altars in their homes, and while claiming their European origins, they strictly observe the catholic religion. Today, in the family cemetery (where I got the pictures), the oldest tomb is to Nicolas Olivier de Montaguere’s. According to the tradition, Nicolas grew up with the king of Dahomey Agonglo (1789-1797). After his adolescence spent in Abomey with the king, he returned to Ouidah in his father’s family home when he continued to deal palm oil . Nicolas and Joseph’s descendants still live in the old compound of their ancestors. They have maintained a position of prestige in the society, and historically occupy important positions in the public administration. Ouidah, Benin.

CLEMENT OLIVIER DE MONTAGUERE, descendant of Olivier de Montaguere in the family cemetery, Ouidah. Clement is a member of this family originally from Marseille, France. His ancestor, Olivier de Montaguere, was the nineteenth steward of the French Fort for Louis XVI. He arrived in Ouidah in 1776. He brought with him his wife and their three children, Joseph, Nicolas and Jean Baptiste and organized the slave trade with the French West Indies, «He disappeared during one of his trips to the Caribbean and he is never returned to Ouidah» said Clement Olivier of Montaguere. Their descendents still live today in the old compound of their ancestor. Unlike many other local families, they have no voodoo altars in their homes, and while claiming their European origins, they strictly observe the catholic religion. Today, in the family cemetery (where I got the pictures), the oldest tomb is to Nicolas Olivier de Montaguere’s. According to the tradition, Nicolas grew up with the king of Dahomey Agonglo (1789-1797). After his adolescence spent in Abomey with the king, he returned to Ouidah in his father’s family home when he continued to deal palm oil . Nicolas and Joseph’s descendants still live in the old compound of their ancestors. They have maintained a position of prestige in the society, and historically occupy important positions in the public administration. Ouidah, Benin. Honorè Feliciano DE SOUZA, CHACHA VIII in the memorial of Chacha I, Ouidah. Honore Feliciano de Souza is the current head of the Aguda community and the direct heir of Don Francisco Felix de Souza, Chacha I (1754-1848), the foremost middle-men in the slave trade between the Kingdom of Dahomey and the Europeans, early XIXth century. To honor their ancestor, the family has a memorial in Singbomey, with the tomb of Chacha I. This memorial existed for many years, but became accessible to the public only in the 1990s. Paradoxically, slavery heritage official projects also helped to promote the memory of the slave merchant Francisco Felix de Souza. According to Honore Feliciano‘s unlikely opinion, “the Chacha was not involved in such a slave trade as this. At the time when the Kingdom of Dahomey was killing people, he preferred to take them to Brazil to make them work. He was in fact saving people and that is the reason why today there is some admiration for him,” he says. “Nowadays, no one would want to be a Chacha. Being Chacha is facing many hardships. I haven’t chosen to be one. On October 1995, everyone gathered here and I was appointed Chacha VIII, I cried that day. It’s a life-long mandate.” Ouidah, Benin.

Honorè Feliciano DE SOUZA, CHACHA VIII in the memorial of Chacha I, Ouidah. Honore Feliciano de Souza is the current head of the Aguda community and the direct heir of Don Francisco Felix de Souza, Chacha I (1754-1848), the foremost middle-men in the slave trade between the Kingdom of Dahomey and the Europeans, early XIXth century. To honor their ancestor, the family has a memorial in Singbomey, with the tomb of Chacha I. This memorial existed for many years, but became accessible to the public only in the 1990s. Paradoxically, slavery heritage official projects also helped to promote the memory of the slave merchant Francisco Felix de Souza. According to Honore Feliciano‘s unlikely opinion, “the Chacha was not involved in such a slave trade as this. At the time when the Kingdom of Dahomey was killing people, he preferred to take them to Brazil to make them work. He was in fact saving people and that is the reason why today there is some admiration for him,” he says. “Nowadays, no one would want to be a Chacha. Being Chacha is facing many hardships. I haven’t chosen to be one. On October 1995, everyone gathered here and I was appointed Chacha VIII, I cried that day. It’s a life-long mandate.” Ouidah, Benin. His majesty MITO DAHO KPASSÈNON, king of Ouidah and supreme head of the voodoo cult, sitting in the Audience hall, Royal Palace. Mito Daho Kpassenon is a member of one of the oldest families of Benin, heir and descendant of King Kpassé, the first one to make business with the Europeans, particularly through the slave trade, when the Portuguese arrived in the Benin Bay around 1580. “According to the oral tradition, KPaté, one of the king’s servants, was fishing crabs on the shore when he saw white people on the beach. He took them to King KPASSE, and from that day they started trading,” tells King Kpassenon. In the early 1990s, relying on the cultural and religious exchanges established during the period of the Atlantic slave trade, and in parallel with the debates aimed at developing the Slave Route Project, he joined the project “Ouidah 92”, the world festival of voodoo culture. Like the president Songlo, by promoting the Vodun religion and the exchanges between Africa and the Americas, he presented slavery and the Atlantic slave trade not as a rupture between generations, families, and traditions but as events that produced continuity across the Atlantic. Ouidah, Benin.

His majesty MITO DAHO KPASSÈNON, king of Ouidah and supreme head of the voodoo cult, sitting in the Audience hall, Royal Palace. Mito Daho Kpassenon is a member of one of the oldest families of Benin, heir and descendant of King Kpassé, the first one to make business with the Europeans, particularly through the slave trade, when the Portuguese arrived in the Benin Bay around 1580. “According to the oral tradition, KPaté, one of the king’s servants, was fishing crabs on the shore when he saw white people on the beach. He took them to King KPASSE, and from that day they started trading,” tells King Kpassenon. In the early 1990s, relying on the cultural and religious exchanges established during the period of the Atlantic slave trade, and in parallel with the debates aimed at developing the Slave Route Project, he joined the project “Ouidah 92”, the world festival of voodoo culture. Like the president Songlo, by promoting the Vodun religion and the exchanges between Africa and the Americas, he presented slavery and the Atlantic slave trade not as a rupture between generations, families, and traditions but as events that produced continuity across the Atlantic. Ouidah, Benin. The apex of the Slaves’ Route is the «GATE OF NO RETURN», the only monument in Ouidah sponsored by the Slave Route Project. Situated at the end of the road, on the beach, the imposing gate was unveiled in November 1995, and still attracts numerous tourists and leading foreign visitors, such as the Brazilian President, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva who visited the monument during his travel to the country in 2006. The monument, designed and ornamented by Beninese artist Fortune Bandeira, evokes the monumental Soviet aesthetics that dominated the country’s public monuments until the beginning of the 1990s. Placed on a large cement platform, higher than the level of the ground, the Gate’s arcade marks the transition between the beach and the Atlantic Ocean, which is visible through it. On each side of the gate, giant copper sculptures created by Gnonnou Dominique Kouass, represent a group of captives breaking their chains. Close to the monument, tourists can stop at a kiosk to buy “African” sculptures, wooden masks, jewellery, and calabashes. In addition to these “authentic” objects, the visitors can also buy actual Vodun fetishes, taken from neighbouring temples. Ouidah, Benin.

The apex of the Slaves’ Route is the «GATE OF NO RETURN», the only monument in Ouidah sponsored by the Slave Route Project. Situated at the end of the road, on the beach, the imposing gate was unveiled in November 1995, and still attracts numerous tourists and leading foreign visitors, such as the Brazilian President, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva who visited the monument during his travel to the country in 2006. The monument, designed and ornamented by Beninese artist Fortune Bandeira, evokes the monumental Soviet aesthetics that dominated the country’s public monuments until the beginning of the 1990s. Placed on a large cement platform, higher than the level of the ground, the Gate’s arcade marks the transition between the beach and the Atlantic Ocean, which is visible through it. On each side of the gate, giant copper sculptures created by Gnonnou Dominique Kouass, represent a group of captives breaking their chains. Close to the monument, tourists can stop at a kiosk to buy “African” sculptures, wooden masks, jewellery, and calabashes. In addition to these “authentic” objects, the visitors can also buy actual Vodun fetishes, taken from neighbouring temples. Ouidah, Benin. Ahi, doing some repairs on the “Slaves’ Route”. The Slaves’ Route is a two-miles road starting in downtown Ouidah, close to a former slave market, and ending at the beach, where the captives were allegedly put on pirogues that brought them to the slave ships. In fact, because the coastal lagoon separated the town from the shore, it is more likely that the captives covered part of the way to the outer shore by canoe. Despite the relative success of the Slaves’ Route, only the local population living in the neighbourhoods is sufficiently audacious to walk along the road. The two-miles road is long and because the traffic is intense and there is no allotted space for pedestrians, it is rather difficult to safely observe the monuments. Indeed, individual tourists experience the Slaves’ Route by zemidjan (local motorcycle taxis). If with groups, they see the route by car or bus, and stop only at the end of the road, at the beach. Ouidah, Benin

Ahi, doing some repairs on the “Slaves’ Route”. The Slaves’ Route is a two-miles road starting in downtown Ouidah, close to a former slave market, and ending at the beach, where the captives were allegedly put on pirogues that brought them to the slave ships. In fact, because the coastal lagoon separated the town from the shore, it is more likely that the captives covered part of the way to the outer shore by canoe. Despite the relative success of the Slaves’ Route, only the local population living in the neighbourhoods is sufficiently audacious to walk along the road. The two-miles road is long and because the traffic is intense and there is no allotted space for pedestrians, it is rather difficult to safely observe the monuments. Indeed, individual tourists experience the Slaves’ Route by zemidjan (local motorcycle taxis). If with groups, they see the route by car or bus, and stop only at the end of the road, at the beach. Ouidah, Benin A detention cell for reluctant slaves, according to Philip Atta-Tawson’s story, Fort William, Anomabu. Philip Atta-Tawson is today the keeper of the place where he lives with his family. In most castles of Ghana, there is a family living and working as a custodian on behalf of the government. An estimated half million of captives were sent from Anomabu to the Americas, among which 30 000 to the French West Indies. In the past, the fort was then used as a jail, then a post office, until it became a national registered site. Anomabu, Ghana

A detention cell for reluctant slaves, according to Philip Atta-Tawson’s story, Fort William, Anomabu. Philip Atta-Tawson is today the keeper of the place where he lives with his family. In most castles of Ghana, there is a family living and working as a custodian on behalf of the government. An estimated half million of captives were sent from Anomabu to the Americas, among which 30 000 to the French West Indies. In the past, the fort was then used as a jail, then a post office, until it became a national registered site. Anomabu, Ghana